[1] Upon hearing of a Muslim having become a Murtad, the Learned (Imam / Sheikh) and family members are expected to call on him / her at least once every day for three days, (or on three separate occasions) in order to coerce and induce him / her back into the fold. Beautiful speech with wisdom (as ordained by Almighty Allah) should be used. Should this person agree to return, he / she will have to follow the same procedure as would apply to a convert to the Faith; that is firstly reject Kufr (disbelief) and then pronounce his Shahadat (Testimony) in the presence of witnesses. A Murtad must also repay the obligatory duties (Fara-id) he had missed. (Salah – Zakaah -Siyam) – Once he / she returns to Islam, Muslims must no longer shun him. The attitude Islam adopts towards a Murtad is that if he dies or is killed, Muslims are not allowed to bath or bury him in their cemetery or to offer prayers for him. This is declared in the Holy Quran in Surah Taubah, Verse 84: “Nor do thou ever pray for any of them that dies nor stand at his grave: for they rejected Allah and his Apostle, and died in a state of perverse rebellion. ” Therefore, a Muslim should not fraternise or befriend a Murtad. (You are allowed to befriend people of other Faiths, but not those who are Murtad.) (One should isolate oneself from family members who have apostated)

Even marriage ties are affected. A wife or a husband of a Murtad or of a Mulhad does not require other grounds for annulling Marriage. A Murtad, having committed Kuf’r, cannot inherit from a Muslim nor a Muslim from him. A directive of the Holy Prophet says, “The Kaafir does not inherit a Muslim’s wealth nor a Muslim a Kaafir’s.” For committing the act of KUFR, one should make TAUBAH— repent sincerely—for three days—earnestly begging Allah for His forgiveness, beseeching Him for His mercy, for He is Oft-forgiving, Most Mercifull — (This is hardly a “punishment” befitting the grievous offence. It is rather an opportunity for those who go astray to invoke His clemency.) — A Kaafir, a Murtad or a Mulhad is permitted back into the fold of Islam, provided he PUBLICLY rejects Kufr beliefs, declares his Kalimah Shahada and makes sincere Taubah.

[2] It is very disturbing to note, therefore that the field of apostasy (and blasphemy) has become a complex syndrome within all Muslim societies which touches a raw nerve and always arouses great emotional outbursts against the perceived acts of treason, betrayal and attacks on Islam and its honour. While there are a few brave dissenting voices within Muslim societies, the threat of the application of the apostasy (and blasphemy) laws against any who criticize its application is an efficient weapon used to intimidate opponents, silence criticism, punish rivals, reject innovations and reform, and keep non-Muslim communities in their place. The violence or threats of violence against apostates in the Muslim world usually derives not from government authorities but from individuals or groups operating with impunity from the government.

[3] In the fourth chapter of Hujjat‑Allah al‑Balighah, [4] Part I, Shah Wali Ullah has categorised the extant compilations of traditions in their order of reliability and importance. He thinks that only al‑Muwatta’ of Imam Malik, Sahih Bukhai and Sahih Muslim deserve to be placed in the first category. The compilations like those of Abu Dawud, Tirmidhi, Ibn Majah and Nasa’i, which are generally included among the Sihah Sittah (the Six Accurate Books) and Musnad of Imam Ahmad, he assigns to the second category. He adds that the Muhaddithin (Experts in Tradition) consider these two categories only to be worthy of reliance and not the books falling in the third and fourth categories such as Musnad of Abi ‘Ali, Musannaf of `Abd‑ur‑Razzaq, Musannaf of Abi Bakr b. Abi Shaibah, Musnad of `Abd b. Hamid, Musnad of Tayalisi, and books by Baihaqi, Tahavi, Tabarani, Ibn Habban, Ibn `Adi, Khatib, Abi Nu’aim, Ibn al‑‘Asakir, Khwarazmi, Ibn Najjar, Dailami, and others. There are also fabricated ahadith, collected and criticised by Mulla ‘Ali Qari and Ibn al Jauzi among others. Traditions themselves are differentiated per se in order of authenticity and reliability. In point of priority they are designated as Mutawatir (continuous) Mustafid (narrated in several ways and accepted), Mash‑hur (reputed), Sahih (accepted as correct) and Hasan (approved), and the lowest tier in this hierarchy is that of Khabar Ahad. The number and reliability of the chain of narrators, its continuity or otherwise, evidence of implementation or rejection, conformity with the Qur’anic letter or spirit as well as with known historical or rational facts, are some of the factors which determine this order of priority. The human factor of lapse of memory or of failure to comprehend fully the circumstances surrounding a tradition is also a pertinent consideration. The classical instance of Hadrat `A’yeshah, the Prophet’s wife, correcting Ibn `Umar (or according to one version, Hadrat `Umar, the Second Caliph, himself) in respect of his opinion that the lamentations of a deceased person’s relatives entail torture in the after‑life for the dead person is very apt in this context. Hadrat `A’yeshah’s comment was that the hadith had not been properly understood or recollected. She explained that in fact the Prophet had passed by a Jewish woman who had died, and had seen her relatives lamenting, when he observed: “They are crying and she is being subjected to torture.” It was wrongly assumed that there was a casual nexus between the two sentences uttered by the Prophet, and she cited the Qur’an : “No bearer of burden can bear the burden of another” (al‑An’am, verse 164). She evidently invoked the principle that a hadith could not possibly contradict a clear text of the Qur’an and interpreted the reported tradition in its light. Shah Wali Allah in his “Iqd al jid” has laid down the principle that Sunnah only explains the Qur’an and can never contradict it.

[4] Shah Wali Ullah in his Hujjat Allah al‑Balighah cites the opinion of `Abdullah b. ‘Abbas, ‘Ala’, Mujahid and Imam Malik to the effect that, however eminent a personality may be, if certain statements of his are accepted, there may be some other statements attributed to him, which it would be necessary to reject. For there is no man except the Prophet whose every saying would be capable of citation as a conclusive argument. Earlier he expresses the categorical view that the basis of some statements ascribed to Sahabah (Companions of the Prophet) is merely “forgetfulness or error”. In the Mukhtasar of Sayyid alSharif al jurjani it is said: “Whatever is related from a Sahabi, either in the form of a saying or in the shape of action, whether narrated by a continuous chain of narrators or not, is not a binding instance.” In the Qamar al-Aqmar Sharh Nur al‑Anwar it is laid down on the authority of Maulana` Abdal‑`Ali Bahr al‑`Ulum, that the mere possibility that a Sahabi (Companion) might have based himself on what he might have heard from the Prophet does not make it obligatory to follow his opinion.There is also the well‑known observation of Imam Shafi.`i regarding the Sahabah : “They were men and so are we.’

[5] Maulana Badr‑i‑`Alam Nadvi in his Tarjuman al-Sunnah says, on the authority of extracts from Imam Shatibi’s al‑Muwafaqat, that the Sunnah occupies a place of secondary importance as compared with the Book of God and that generally it can be asserted firmly that the Sunnah cannot be placed on the same level with the Qur’an in point of regard and reverence. This is the reason why Taftazani in his Talwih lays it down as a guiding principle that in case of conflict with the text of the Qur’an, Khabar al‑Wahid (a tradition related by one person from another individual or by one person from a group or by a group from one person, so long as the number of narrators is less than those in the case of Hadith Mash-hur [reputed tradition]) will be rejected. Such a hadith is said to be only Mufid‑i‑Zann (as raising only a presumption).

[6] Official Fatwa of the Mufti of Greater Washington, Sheikh Mohammed Ali Al-Hanooti

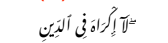

on Apostasy: The issue of apostasy falls under the umbrella of man’s free will, freedom of expression and belief. The Holy Qur’an states unequivocally that nobody can be compelled to either become a Muslim or remain one. In Surah 4: 137, Allah says, “Behold, as for those who come to believe, and then deny the truth, and again come to believe and again deny the truth and thereafter, grow stubborn in their denial of the truth, God will not forgive them, nor will He guide them in any way.” This ayah very clearly shows that even after rejecting Islam twice, no punishment is prescribed for the apostates.

The punishment for apostasy mentioned in Islamic literature is derived from hadiths whose authenticity is not certain (as these hadiths are ahad -from one source, but not mutawatir- from a consensus of sources). Even among those scholars who accept them as authentic, there is vast difference of opinion on the interpretation and elaboration of the hadiths. Such hadiths have been traditionally cited as justification for executing apostates, but these were circumstantial rulings where legal authorities of that time deemed the punishment justified, as the act of apostasy in question, or in some cases, mass apostasy was comparable to treason or to an organized crime outfit, where the apostates would ally themselves with the opponents of the state.

Such hadiths, which have, in the past, been cited to justify punishment for apostasy, therefore, cannot stand against the Qur’an, which provides no textual evidence for such action. On the contrary, the Qur’an states in Surah 10: 99: “If it had been the will of your Lord that all the people of the world should be believers, all the people of the world would have believed! Would you then compel them against their will to believe?”

In conclusion, the Qur’an is the definitive clear authority for protecting the rights of an individual in expressing himself in faith and supersedes any of the distorted interpretations of the hadiths in question. Executing a person because of conversion to another faith contradicts the Qur’an, the ultimate source of Shari’ah.

[7] To everyone acquainted with Islamic law it is no secret that according to Islam the punishment for a Muslim who turns to kufr (infidelity, blasphemy) is execution. Doubt about this matter first arose among Muslims during the final portion of the nineteenth century as a result of speculation. Otherwise, for the full twelve centuries prior to that time the total Muslim community remained unanimous about it. The whole of our religious literature clearly testifies that ambiguity about the matter of the apostate’s execution never existed among Muslims. The expositions of the Prophet, the Rightly-Guided Caliphs (Khulafa’-i Rashidun), the great Companions (Sahaba) of the Prophet, their Followers (Tabi’un), the leaders among the mujtahids and, following them, the doctors of the shari’ah of every century are available on record. All these collectively will assure you that from the time of the Prophet to the present day one injunction only has been continuously and uninterruptedly operative and that no room whatever remains to suggest that perhaps the punishment of the apostate is not execution.

Some people have been influenced by the so-called enlightenment of the present age to the point that they have opened the door to contrary thoughts on such proven issues. Their daring is truly very astonishing. They have not considered that if doubts arise even about such matters which are supported by such a continuous and unbroken series of witnesses, this state of affairs will not be confined to one or two problems. Hereafter anything whatever of a past age which has come down to us through verbal tradition will not be protected from doubt, be it the Qur’an or ritual prayer (namaz) or fasting (roza). It will come to the point that even Muhammad’s mission to this world will be questioned. In fact a more reasonable way for these people, rather than creating doubt of this kind, would have been to accept as fact what is fact and is proven through certified witnesses, and then to consider whether or not to follow the religion which punishes the apostate by death. The person who discovers any established or wholesome element of his religion to conflict with his intellectual standards and then tries to prove that this element is not really a part of the religion, already proves that his affliction is such that, “You cannot become a kafir (infidel); since there is no other choice, become a Muslim.” In other words, though his manner of thought and outlook has deviated from the true path of his religion, he insists on remaining in it only because he has inherited it from his forefathers. Maudoodi later adds that all four Schools without doubt agree on the point that the punishment of the apostate is execution. He further adds “let us suppose the commandment is not found in the Qur’an; still the large number of Hadith, the decisions of the Rightly-Guided Caliphs and the united opinions of the lawyers suffice fully to establish this commandment.

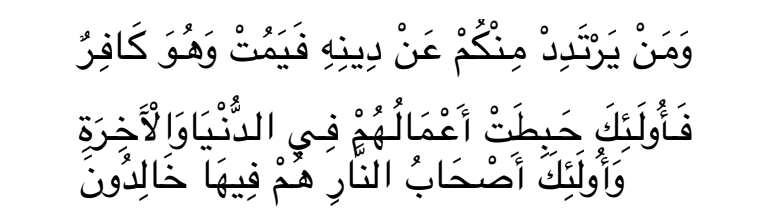

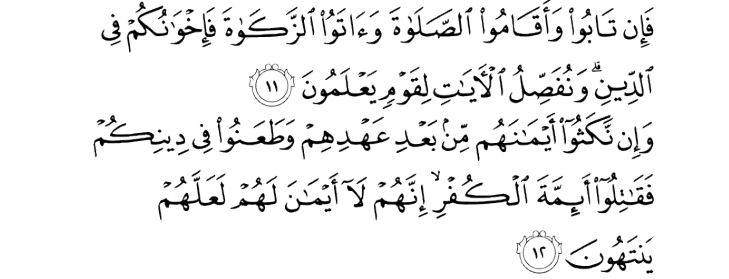

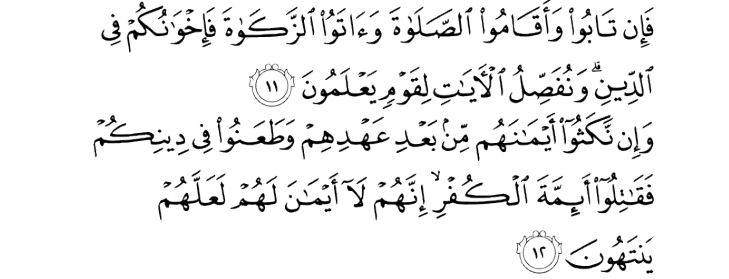

But (even so), if they repent, establish regular prayers, and practise regular charity,- they are your brethren in Faith: (thus) do We explain the Signs in detail, for those who understand.(11) But if they violate their oaths after their covenant, and taunt you for your Faith,- fight ye the chiefs of Unfaith: for their oaths are nothing to them: that thus they may be restrained.

[9] This is the command of the Prophet:

1. “Any person (i.e., Muslim) who has changed his religion, kill him.”

This tradition has been narrated by Abu Bakr, Uthman, Ali, Muadh ibn Jabal, Abu Musa Ashari, Abdullah ibn Abbas, Khalid ibn Walid and a number of other Companions, and is found in all the authentic Hadith collections.

2. Abdullah ibn Masud reports: (the second hadith)

The Messenger of God stated: In no way is it permitted to shed the blood of a Muslim who testifies that “there is no god except God” and “I am the Apostle of God” except for three crimes: a. he has killed someone and his act merits retaliation; b. he is married and commits adultery; c. he abandons his religion and is separated from the community.

3. Aisha reports:

The Messenger of God stated that it is unlawful to shed the blood of a Muslim other than for the following reasons: a. although married, he commits adultery or b. after being a Muslim he chooses kufr, or c. he takes someone’s life.

4. Uthman reports:

I heard the Messenger of God saying that it is unlawful to shed the blood of a Muslim except in three situations: a. a person who, being a Muslim, becomes a kafir; b. one who after marriage commits adultery; c. one who commits murder apart from having an authorization to take life in exchange for another life.

Uthman further reports:

I heard the Messenger of God saying that it is unlawful to shed the blood of a Muslim with the exception of three crimes: a. the punishment of someone who after marriage commits adultery is stoning; b. retaliation is required against someone who intentionally commits murder; c. anyone who becomes an apostate after being a Muslim should be punished by death.

All the reliable texts of history clearly prove that Uthman, while standing on the roof of his home, recited this tradition before thousands of people at a time when rebels had surrounded his house and were ready to kill him. His argument against the rebels was based on the point of this tradition that apart from these three crimes it was unlawful to put a Muslim to death for a fourth crime, “and I have committed none of these three. Hence after killing me, you yourself will be found guilty.” It is evident that in this way this tradition became a clear argument in favour of Uthman against the rebels. Had there been the slightest doubt about the genuineness of this tradition, hundreds of voices would have cried out: “Your statement is false or doubtful!” But not even one person among the whole gathering of the rebels could raise an objection against the authenticity of this tradition.

5. Abu Musa Ashari reports:

The Prophet appointed and sent him (Abu Musa) as governor of Yemen. Then later he sent Muadh ibn Jabal as his assistant. When Muadh arrived there, he announced: People, I am sent by the Messenger of God for you. Abu Musa placed a cushion for him to be comfortably seated.

Meanwhile a person was presented who previously had been a Jew, then was a Muslim and then became a Jew. Muadh said: I will not sit unless this person is executed. This is the judgement of God and His Messenger. Muadh repeated the statement three times. Finally, when he was killed, Muadh sat.

It should be noted that this incident took place during the blessed life of the Prophet. At that time Abu Musa represented the Prophet as governor and Muadh as vice-governor. If their action had not been based on the decision of God and His Messenger, surely the Prophet would have objected.

6. Abdullah ibn Abbas reports:

Abdullah ibn Abi Sarh was at one time secretary to the Messenger of God. Then Satan seized him and he joined the kuffar. When Mecca was conquered the Messenger of God ordered that he be killed. Later, however, Uthman sought refuge for him and the Messenger of Allah gave him refuge.

We find the commentary on this last incident in the narration of Sad ibn Abi Waqqas:

When Mecca was conquered, Abdullah ibn Sad ibn Abi Sarh took refuge with Uthman ibn Affan. Uthman took him and they presented themselves to the Prophet, requesting: O Messenger of God, accept the allegiance of Abdullah. The Prophet lifted his head, looked in his direction and remained silent. This happened three times and he (the Prophet) only looked in his direction. Finally after three times he accepted his allegiance. Then he turned towards his Companions and said: Was there no worthy man among you who, when he saw me withholding my hand from accepting his allegiance, would step forward and kill this person? The people replied: O Messenger of God, we did not know your wish. Why did you not signal with your eyes? To this the Prophet replied: It is unbecoming of a Prophet to glance in a stealthy manner.

7. Aisha narrates:

On the occasion of the battle of Uhud (when the Muslims suffered defeat), a woman apostatized. To this the Prophet responded: Let her repent. If she does not repent, she should be executed.

8. Jabir ibn Abdullah narrates:

A woman Umm Ruman (or Umm Marwan) apostatized. Then the prophet ordered that it would be better that she be offered Islam again and then repent. Otherwise she should be executed. A second report of Bayhaqi with reference to this reads: She refused to accept Islam. Therefore she was executed.

[10] Dr. Sheikh Abdur Rehman (Died 1990) was a Chief Justice of Pakistan. He did his MA from University of Punjab, BA Hons from Oxford and Ph.D. in Law from Cairo.

In 1958 he was made the Judge, Supreme Court of Pakistan. Besides his Professional career he remained the Chairman Central Urdu Board Lahore, Director Institute of Islamic Culture, Lahore, Member Bazm-i-Iqal and the Board for the Advancement of Literature and President Pakistan Arts Council. Rehman has three books to his credit; TARJUMAN-I-ISRAR (Urdu translation in verse of Iqbal’s ISRAR-I-KHUDI, SAFAR a collection of Urdu poems, and Punishment Of Apostasy In Islam.

[11] “The principal hadith on which the case for the death sentence for apostasy is built up is the one narrated by Ibn ‘Abbas in the words: “Whosoever changes his religion, slay him.” This is the version given by Bukhari in his Sahih ‑ “Kitab al Jihad fi Istitabat al‑Murtaddin”. To it is annexed the story of Hadrat ‘Ali burning to death a number of Zanadiqah (heretics), and Ibn ‘Abbas, on being informed of the incident, is stated to have remarked that he would not have burnt them but merely killed them, for the Prophet had forbidden the burning of human beings. He then recited this hadith. The same hadith is also traced to Hadrat `Ayeshah by al‑Tabarani in his Mu`jamat al‑Wast. According to another narrator, Mu’awiyah b. Hidah, as recorded in al‑Tabarani’s Mu`jamat al‑Kabir, the full hadith should read: “Whosoever changes his faith, slay him. Verily Allah does not accept repentance from His servant who has adopted disbelief after having accepted Islam.” The latter part of this version apparently contradicts the Qur’anic texts, which we have already noticed, and is unreliable. None of these sources, however, indicate the circumstances which provided the occasion for this qauli (verbal) hadith. On the face of it, the hadith is mujmal ‑ a summary statement ‑ and calls for further elucidation.

Difference of opinion prevails among Doctors of Law as to whether this hadith applies to a woman apostate or not. Al‑Samara’i mentions that Imam Malik, al‑Auza`i, Imam al‑Shafi’i and al‑Laith b. Sa’d accepted this hadith as sufficient authority for killing a Muslim woman who leaves the fold of Islam, having regard to the general nature of the expressions used therein. However, al-Thauri, Imam Abu Hanifah and his followers, Ibn Shabramah, Ibn `Aliyyah, ‘Ata’ and al‑Hasan excluded women from its scope. Their argument was that Ibn ‘Abbas, the principal narrator of the hadith, had himself declared that a female apostate should not be killed, as the Prophet had forbidden the slaying of women in wars. The Shafi`is, the Hanbalis, the Zaidis and the Malikis place men and women on the same footing, in this respect, but the Hanafis and the Imamiyyah Shi`ahs say that the woman will be imprisoned till she repents. Sarakhsi, among the Ahnaf, apparently took the view that a woman who was possessed of sound judgment and capacity to give orders can also be condemned to death for apostasy, though, normally, she would be immune from that sentence. Al‑Samara’i has dealt with the question at length, in Ahkam al‑Murtadd. Other authorities too have pointedly referred to this exemption. The Maliki Ibn al‑Qudamah, in his al‑Mughni, says that a Muharibah woman is not to be killed but only imprisoned.

There are other recognised exceptions that still further restrict the scope of this tradition. Dr Muhammad Hamidullah, in his Muslim Conduct of State, has summarised the position in these words: “In case an insane person, a delirious, a melancholy, a perplexed man, a minor, one intoxicated or who had declared his faith in Islam under coercion and a person whose faith in Islam has not been known or established, were to become apostate, they would not suffer the supreme penalty. So too, an apostate woman and a hermaphrodite, according to the Hanafi school of Law, would not be condemned to death but imprisoned and even physically tortured. An old man from whom no offspring is expected is also excepted.” In support of this statement he refers to Kasani, Bada’i`, VII, 134; Sarakhsi, Mabsut, X, 123 ; Ibn `Abidin, Radd al‑Muhtar, III, 246 and 326‑71; Abu Yusuf, Kharaj, p. 111 ; Sarakhsi, Sharh al‑Usul, Chapter “al Juz’ Yalhaqat al‑Takdhib.” These exemptions also find mention in various chapters of Ahkam al-Murtadd by al‑Samarra’i. The Fath al‑Bari too adverts to two exceptions, viz. of a hypocrite and one forced to the faith.

If then the accepted position be that the hadith is not to be taken literally and is subject to several qualifications and the circumstances in which the relevant words were uttered by the Prophet are not precisely known, would it be too much to take the next step and suggest that there is also underlying the hadith a tacit assumption that the person concerned must be guilty of Muharabah (active hostility)? This would have the merit of bringing the purport of the hadith into conformity with verse 34 of Surat al‑Maidah: “The only reward of those who wage war against Allah and His Messenger and strive to create disorder in the land, is that they may be slain or crucified ….”

The fact that this hadath exists in a verbally different version, though carrying the same sense, may perhaps justify the criticism that narrators may have retained what they understood to be the purport of the tradition and may have failed to recollect the exact words and the full circumstances surrounding the origin of the saying. This consideration may be allowed to fortify the attempt at its reconciliation with the Qur’anic text by evocation of its underlying assumption that the person involved must have joined those warring against the Muslims.

[12] The next tradition to be considered has several verbal variants and, in some of them, the additional words are very significant. The formulation by ‘Abdullah b. Mas’ud runs in these terms

(1) The Prophet (on him be blessings and peace of God) said: It is not lawful to shed the blood of a person professing Islam, who testifies that there is no god but Allah and that I am the Messenger of Allah, except in three cases: life for a life, or a married person guilty of adultery or a person who separates from his faith and deserts his community. (Bukhari, “Kitab al‑Diyat,” “Bab al‑Nafs bi al‑Nafs”). A similar version exists in Tirmidhi’s Sunan.

(2) In the same “Kitab al‑Diyat,” “Bab al‑Qasamah,” Bukhari records another version narrated by Abu Qulabah : “The Messenger did not put to death anyone by way of Hadd (prescribed punishment) except for one of three antecedents: a person who commits murder of his own free will shall be killed, (so also) a person who commits fornication after marriage or a person who fights Allah and His Messenger and becomes an apostate from Islam.”

(3) A summary version is attributed to Hadrat A’yeshah in Sunan al‑Nasa’i, in which the relevant words for the third category of persons are “one who commits apostasy, after accepting Islam”. A full version is, however, also contained in Nasa’i’s Sunan, which brings out the element of hostility to the community on the part of the apostate. An alternative detailed version is assigned to Hadrat `A’yeshah by Abu Dawud (“Kitab al‑Hudud,” “Bab al‑Hukm fi man Artadda).” Therein the third category is defined as comprising of a person “Muhariban bi’Ilah wa Rasulahu fa innahu yuqtal au yuslab au yunfa,” i.e. “who fights Allah and His Messenger and he will be killed or crucified or banished from the land” words reminiscent of verse 35 of Surat al‑Ma’idah.

(4) Two versions are traced to Hadrat `Uthman, the Third Caliph. One says: “I heard the Messenger of God (on him be peace and blessings of God) say: It is not lawful to shed the blood of a Muslim except in one out of three cases: a person who apostatizes after accepting Islam or who fornicates after marriage or one who kills a person without retaliation for murder of another (Nasa’i, Sunan: “Bab Dhikr ma yuhillu bihi dam al‑Muslim”). In the second version attributed to Hadrat Uthman, also in the same Bab in Nasa’i, the relevant words are: “Or one who commits apostasy after having believed.” It is said that Hadrat `Uthman had proclaimed this tradition to the crowd that had surrounded his house in order to assassinate him.

(5)Somewhat akin to the theme of this hadith is the one given by Abu Dawud on the authority of Jam: “When a servant of God runs away to polytheism, shedding of his blood becomes lawful.” In the Zamindar of 8 October 1924, M. Siraj Ahmad mentions a version included in the Sunan of Nasa’i in which the relevant words are: “One who leaves the community and cuts it asunder.” There are some lesser compilations of hadith which mention similar versions, but they need not be noticed.

(6)Yet another version states: “The blood of a Muslim who professes that there is no god but Allah and that I am His Messenger, is sacrosanct except in three cases: a married adulterer; a person who has killed another human being; and a person who has abandoned his religion, while splitting himself off from the community (mufariq li’l-jama’ah)”. As will be noted, this Hadith makes clear that the apostate must also boycott the community (mufariq li’l-jama’ah) and challenge its legitimate leadership, in order to be subjected to the death penalty.

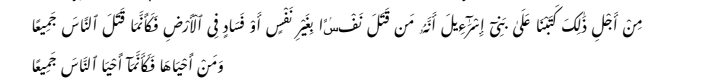

It is noteworthy that the Qur’an has strictly disallowed the imposition of the death penalty except in two specific cases. One of them is where the person is guilty of murdering another person and the other is where a person is guilty of creating unrest in the country (fasa’d fil-ardh) like being involved in activities that create unrest in a society, for example activities like terrorism etc. The Qur’an says:

On that account: “We ordained for the Children of Israel that if any one slew a person – unless it be for murder or for spreading mischief in the land – it would be as if he slew the whole people

Whoever kills a person without his being guilty of murder or of creating unrest in the land, is as though he kills the whole of mankind……….” (Surah 5: 32)

In view of the variations in different versions of the hadith it may be legitimate to infer that some of the narrators merely recollected its general sense without preserving the verbal integrity of the hadith. As Imam Shafi’i has remarked in his al‑Risalah concerning differences in reports from the Prophet, “Sometimes he (the Prophet) was questioned about something and he used to give a reply in accordance with the question; sometimes the narrator conveyed fully what he had heard and sometimes summarised, so that, on occasions, the full purport was conveyed and, on occasions, this did not happen. Sometimes, a person merely reported that part of the hadith which the Prophet had uttered as his reply, because he was himself not present when the question was asked and which occasioned the answer.” With such possibilities open, an attempt to read together all these variant versions so as to get the full picture would be a process which would carry us nearer to the truth. It follows that the delinquents contemplated in the hadith are those who were not merely renegades from the faith but also in active opposition to the Muslims, having joined the warring disbelievers’ camp. Their case would thus fall within the purview of verse 33 of Surat al‑Ma’idah and their condemnation would be in harmony with the letter as well as the spirit of the Qur’anic text. The present writer finds that this view receives corroboration from the opinion of Maulana Abu’l‑Wafa’ Thana’ Ullah, as has, been mentioned elsewhere.

[13] It has been seen that even the strongest bulwark of the orthodox view, viz. the Sunnah, when subjected to critical examination in the light of history, does not fortify the stand of those who seek to establish that a Muslim who commits apostasy must be condemned to death for his change of belief alone. In instances in which apparently such a punishment was inflicted, other factors have been found to co‑exist, which would have justified action in the interest of collective security. As against them, some positive instances of tolerance of defections from the Faith, with impunity for the renegades, suggest that the Prophet acted strictly in conformity with the letter and the spirit of the Qur’an, and mere change of faith, if peaceful, cannot be visited with any punishment. The sayings of the Prophet, on which the whole edifice of orthodox reasoning is raised, in the absence of a knowledge of the surrounding circumstances, must be construed in a sense which would make them consistent with the Book of God, for it is unimaginable that the Prophet could have gone against any Qur’anic text. There is no doubt a section of `Ulama’ who make the Sunnah the final arbiter in every case of seeming or real conflict with the Qur’an ‑ their claim is: “Al‑Sunnah qadiyah `ala’l‑Kitab” ‑ The Sunnah is the judge over the Book. This is not accepted by some of the best minds among the Muslim scholars, past or present, and such a doctrine would indeed strike an unconscionable blow at the integrity and pristine purity of the Qur’an

[14] Mahmud Shaltut, the late Grand Imam of Al-Azhar Unilversity argued that a worldly punishment for apostasy was not mentioned in the Qur’an and whenever it mentions apostasy it speaks about a punishment in the Hereafter. In a book on the issue, Abdullah Saeed and Hasan Saeed argue that Islamic law that calls for death for apostasy is in conflict with a variety of fundamentals of Islam. They contend that the early development of the law of apostasy was essentially a religio-political tool, and that there was a large diversity of opinion among early Muslims on the punishment.

Medieval Muslim scholars Sufyan al- Thawri and a modern like Hasan at-Turabi, also have argued that the hadith used to justify execution of apostates should be taken to apply only to political betrayal of the Muslim community, rather than to apostasy in general. These scholars argue for the freedom to convert to and from Islam without legal penalty.

A number of Islamic scholars from past centuries, Ibrahim al-Naka’I, Sufyan al-Thawri, Shams al-Din al-Sarakhsi, Abul Walid al-Baji and Ibn Taymiyyah, have all held that apostasy is a serious sin, but not one that requires the death penalty. In modern times, Mahmud Shaltut, Sheikh of al-Azhar, and Dr Mohammed Sayed Tantawi have concurred.

There are some medieval Islamic jurists, albeit a minority notably the Hanafi jurist Sarakhsi (d. 1090), Maliki jurist Ibn al-Walid al-Baji (d. 494 AH) and Hanbali jurist Ibn Taymiyyah (1263–1328), who held that apostasy carries no legal punishment.

[16] Jabir ibn Abdilla narrated that a Bedouin pledged allegiance to Muhammad for Islam (i.e. accepted Islam) and then the Bedouin got fever whereupon he said to Muhammad “cancel my pledge.” But Muhammad refused. He (the Bedouin) came to him (again) saying, “Cancel my pledge.” But Muhammad refused. Then he (the Bedouin) left (Medina). Muhammad said, “Madinah is like a pair of bellows (furnace): it expels its impurities and brightens and clear its good.” [Sahih al-Bukhari, Vol. 9, #

318] .

Abd Allah ibn Abi Sarh, the foster brother of Uthman ibn Affan, and one-time scribe of the Prophet is another example. The Prophet forgave him when Uthman interceded on his behalf. Other cases included that of al-Harith ibn Suwayd and a group of people from Mecca who embraced Islam, renounced it afterwards, and then re-embraced it. Their lives too were spared. Ibn Taymiyyah, who has recorded this information, added that ‘these episodes and similar other ones are well-known to the scholars of Hadith.

But (even so), if they repent, establish regular prayers, and practise regular charity,- they are your brethren in Faith: (thus) do We explain the Signs in detail, for those who understand.(11) But if they violate their oaths after their covenant, and taunt you for your Faith,- fight ye the chiefs of Unfaith: for their oaths are nothing to them: that thus they may be restrained.

But (even so), if they repent, establish regular prayers, and practise regular charity,- they are your brethren in Faith: (thus) do We explain the Signs in detail, for those who understand.(11) But if they violate their oaths after their covenant, and taunt you for your Faith,- fight ye the chiefs of Unfaith: for their oaths are nothing to them: that thus they may be restrained.